Now This is Surreal!

Our current situation lives up to a word that had lost all meaning.

Not since irony has a concept been as abused in popular usage as surrealism. Once a calculated attempt to escape the logic that produced the mechanized horrors of a world war, “surreal” now roughly means “strange.” Typically it is used to describe what it feels like to be on television.

In part, this is a measure of the movement’s popular success. Through figures like Salvador Dali, surrealism became a brand — like Warhol’s pop art — that came to mean simply “out of the ordinary.” When the expected is exceeded in ways we cannot immediately describe, we grasp for the next level. The 11 on the reality scale. This is surreal. That’s what we say.

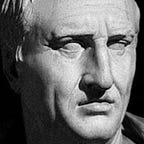

Surrealism as a proper movement wasn’t just about non-reality, however. It was about something, a statement we can make with confidence since it said what it was about, usually via manifesto. As Andre Breton wrote in one of these, it aimed to “resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality.” The attempt at this resolution followed quickly, and inevitably, on the purely negative moment of Dada, in which Breton also participated. Like most negative movements — from Socrates to the Sex Pistols — Dada was exhilarating but unstable. Anti-foundationalism leads to a hunger for foundations…